The Talent Trap

What NOT to tell someone who is good at something (and what we might say instead)

It’s a delicate business, no doubt, nurturing talent. For years I failed to look after my own. The people around me didn’t help.

When I took my first journalism job, straight out of university, my news editor wrote in an appraisal that I was: “A natural born writer.” I liked the sound of this. I put it at the top of my resume. I wore it as a badge of honour.

It was a pattern that repeated throughout my journalism career. At every newspaper I worked for I won praise for the clarity and concision of my writing.

So you see, a lot of damage had already been done.

But it was about to get a whole lot worse.

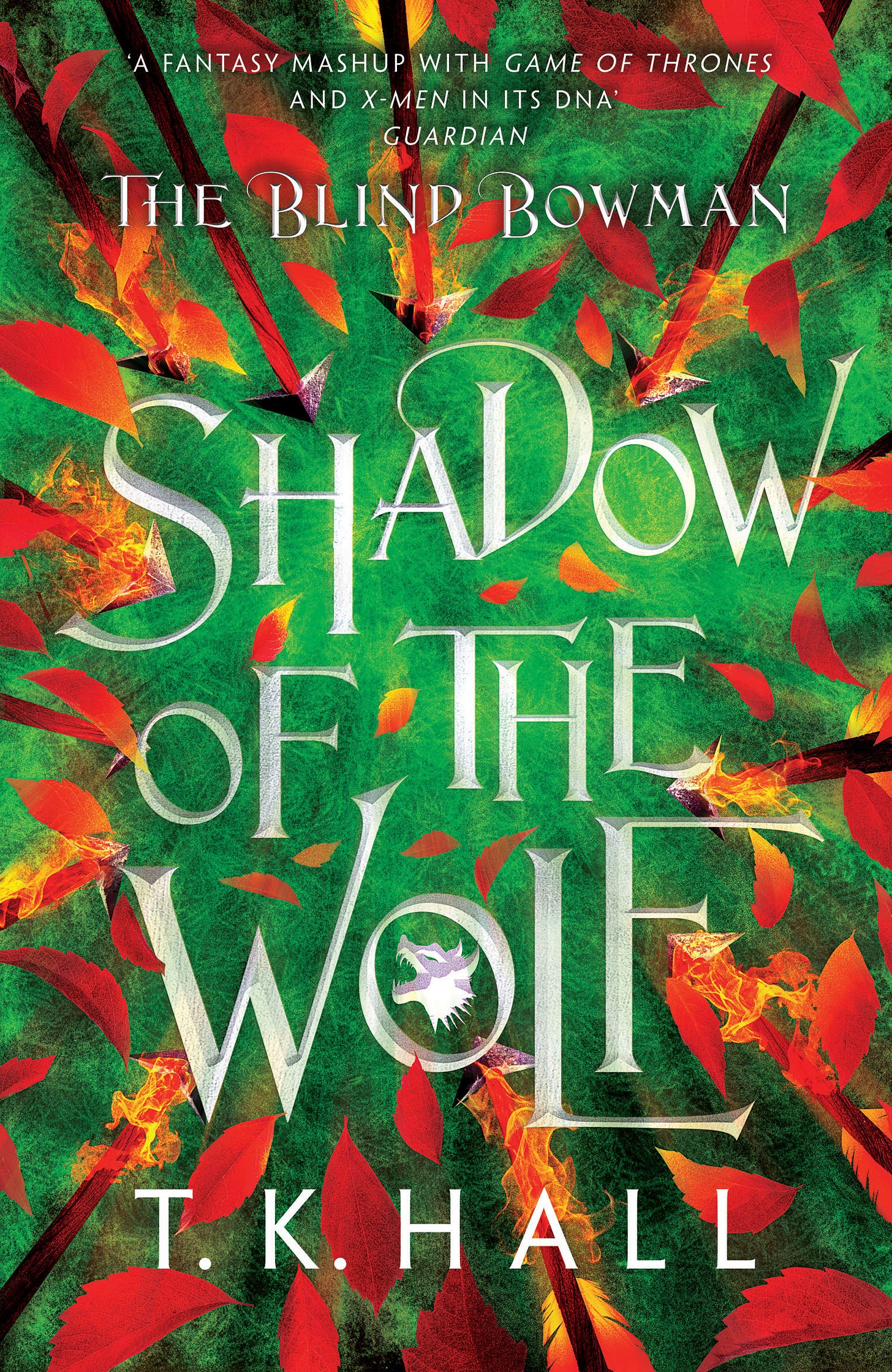

Because my first novel, Shadow of the Wolf, had just earned a book deal. My publishers, David Fickling Books, announced in a press release: “We believe that Tim [Hall] has it in him to be a huge world-renowned writer.”

Now I was really in trouble.

When someone is repeatedly praised for their talent, two things start to happen. Firstly, they slack off. In my case, when my publisher said I ‘had it in me’ to be a big success, what I actually heard was I ‘will be’ a big success. My triumph was fated. I could afford to relax.

To achieve true excellence in anything – certainly something as psychologically and technically demanding as writing novels – requires an extraordinary level of dedication and focus. You must view every writing session as a vital opportunity to test yourself and improve.

Unconsciously, I stopped approaching my writing that way. I didn’t become lazy, exactly, but I was less diligent. Why put myself through an exacting regimen, day after day, hour after hour, when success was already guaranteed?

The second thing that happens, when we’re told how very gifted we are, is even more damaging. In his brilliant book, Bounce, Matthew Syed shows what results when children are praised solely for their talents. They begin to base their whole sense of self around being talented. They then stop challenging themselves, preferring easy tasks to hard ones – or preferring not to try at all, in case they should fail and prove themselves not so exceptional after all. (Children who are praised for their effort, in contrast, push themselves to ever greater heights).

In retrospect, something like this happened to me. After being told, repeatedly, that I was a gifted writer and storyteller, I built my ego around that idea. But the ego is fragile, and easily frightened. It fears, above all, being unmasked as an imposter.

It took me years to write my second novel, Dark Fire. I think part of me was afraid to finish it. I feared, deep down, that my publisher and everyone else would read it and then say: “Oh, we made a mistake. He’s not gifted after all. He’s a fraud.”

That badge of honour I had worn for so long – “natural born writer” – what would I be without it?

All those people who praised my talents did so out of admiration and kindness. And make no mistake, I was fully complicit. I had an inbuilt arrogance (fed by deeper insecurities) that amplified any hint that I might be special or somehow destined for greatness.

Nonetheless, I see now how counterproductive such praise can be.

What my editors and publisher should have told me instead was something like this: “If Tim Hall works really, really hard, if he practices and practices and practices, day after day, year after year, and he stays open to the guidance of others, than he might, just might, achieve something with these abilities he’s learning to develop.”

Not so snappy for the press release; but much more useful for me to hear.

What is talent in any case? Good writing results from iteration. From fastidious reworking of the material at hand, taking out the parts that don’t work, and moving forwards with the parts that do. Repeating ad infinitum.

All this requires commitment, concentration, and unstinting effort. A writer’s task is to train these attributes; forget any thought of innate talent.

So that’s what I’m trying to do. I’m focusing on the words on the page. Getting them down, putting them into good shape, doing it again. Enjoying the process.

Where it leads is anyone’s guess. Whether I ever become “a huge world-renowned author” no longer seems particularly important. I’ll do the work, keep practicing, and remember that I’m always just beginning.

Thanks for joining me on the journey - and happy reading!

Tim

Related reading: Matthew Syed: Bounce: The Myth of Talent and the Power of Practice

If you enjoyed this article, here are a couple more you might like:

And don’t forget to check out the start of the Blind Bowman trilogy, Shadow of the Wolf, which SFX Magazine called “wild, weird and wonderful,” and bestselling author Sally Green pronounced her “favourite book of the year.”

Ultimately, I'm not even sure what talent looks like when it comes to writing and storytelling (which probably means I don't much). In any case, yes, practice is the only thing we can really control. So long as we're showing up diligently, we can safely forget the rest. Wishing you the very best of luck with your own practice...

Tim, your story sounds familiar. I wish someone could have told me a long time ago what I was doing right. Critical parents, “Such a shame you aren’t living up to your potential, you’re so talented”. Later, as an adult, I made sure to sneak that last little factoid into every conversation. But then someone dropped the bomb, something I wish I'd heard a long time ago. “Talent is ZIP without ability." I was shocked. Isn't ability a given?? (happens when you don't belong to a writer's group). And another thing I began to realize through much “pain and suffering”: without a game plan, without discipline (nasty word), I was constantly second-guessing myself, stopping and starting, over and over again. So all this so-called “talent” and I had nothing to show for it—nothing I wanted anyone to see anyway—and that realization beat me into the ground. Where I needed to be. Everyone starts at ground ZERO. Everyone. So now I’m starting over but for the first time in my life I don’t feel like an imposter. I feel like I’m really, truly getting somewhere.