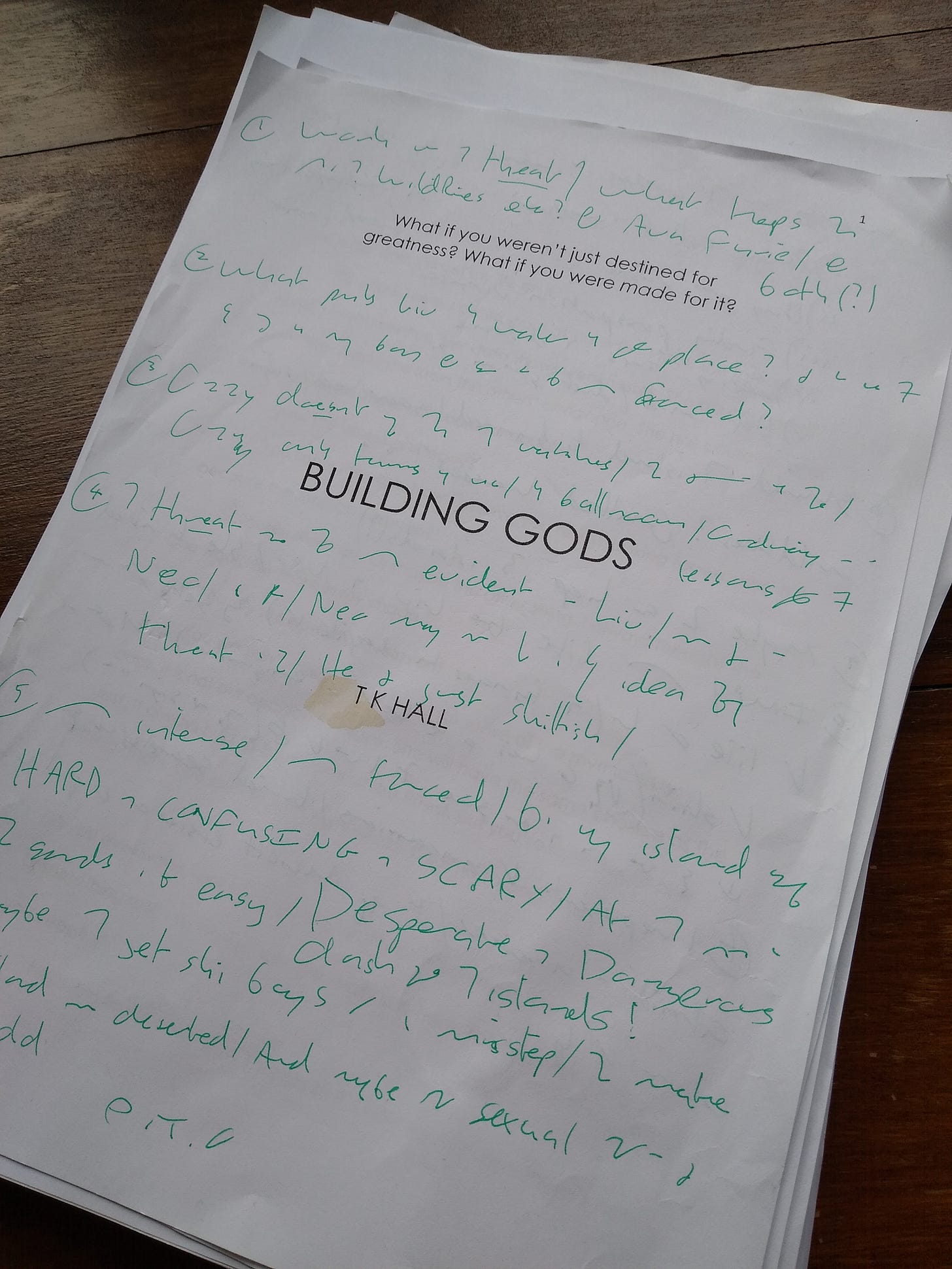

In theory, my next novel promised to be a glorious thing. I was thinking of it as part Bond, part Bourne, with a bit of The Hunger Games thrown in. Thematically, it would be a crashing together of future tech and ancient myth. I was going to call it Building Gods.

I’d done the research, listening to dozens of podcasts on A.I. and reading books on posthumanism. I’d even taken a trip to Athens, where I thought the story would begin.

Finally, it was time to sit down and start writing.

At first it seemed to go okay. The dialogue was a bit stilted, but this was a first draft after all and the characters were still finding their feet.

I reminded myself of the story’s potential and kept going, writing a steady 1,500 words a day.

But then, about a hundred pages in...I just stopped.

At first I wasn’t sure why. The story just seemed to run out of steam.

So I took a step back. I sent the pages off to my publishers, David Fickling Books. My editors, Anthony Hinton and Meggie Dennis, agreed to meet so we could talk through what we had so far.

The first thing Anthony asked me once we’d sat down was: “How are you feeling about the story?”

To which I heard myself respond: “I hate it.”

Until the words left my mouth, I hadn’t realised I felt so strongly. I had the suspicion, even as I was writing those hundred pages, that the story was falling flat. But yes, now I saw it was far worse than that. The manuscript in front of me was an lifeless lump.

Anthony and Meggie are far too nice to admit they hated it too. They would only agree that so far it had failed to come fully alive.

It wasn’t irredeemable, they insisted. The central premise was intriguing, and the characters showed potential. There were all sorts of ways we might try to make it work.

So then, I thought, mentally rolling up my sleeves, we’d better get on with it. After all, what other option was there? I’d started something, was already well invested in it, so what could I do except battle on to the end?

But then Meggie said something that turned everything on its head. She said: “You’ve got to want to fix it. It might sound cheesy, but your heart needs to be in it.”

Immediately, I understood what she meant. During the writing of my Blind Bowman novels, whenever I reached the end of a draft I would sit back and read the manuscript and know it was broken. Drafts always need fixing.

But the fact is, with those books, once I’d got over the initial disappointment that a draft wasn’t as good as I wanted it to be, I couldn’t wait to start making it better. I was excited to start solving its problems.

In a strange sort of way, I came to love the problems, because they presented an energising challenge. And I knew that once the solutions showed themselves, and the story clicked into a new and better shape, those were the most satisfying moments of all.

But with this project, Building Gods, it felt different. When I looked at this faulty manuscript, instead of an eager urge to fix it, I felt...nothing. Indifference.

I had told my editors I hated the story, but that wasn’t really it. If I’d truly loathed what I’d written, then I’d at least have something to fight back against. What I saw in front of me excited no emotion of any kind. There was nothing there worth doing battle with.

So where did we go from here? Turning my back on the story surely wasn’t an option. An essay came to mind by author and writing tutor

. He said the best piece of writing advice he had ever been given was to “finish things.”I mentioned this to my editors. Anthony said: “The reason that’s good advice is that finishing something is hard. You need to know you’re not just procrastinating.”

But how to tell the difference? How to know when it’s time to redouble your efforts, and when you’re flogging a dead horse?

Well, as Meggie pointed out, as with most decisions in life, your heart will tell you. Do you want to fix the manuscript? Do you burn to make it work? If not, where is the energy going to come from? Completing a novel takes months of sustained focus. You could slog your way to the finish line, maybe, but it will be a joyless experience, and no way to make your words sing.

Finally accepting all this, I decided to go no further with Building Gods. I won’t say it felt good. Part of me is still mourning for a story that will now never exist.

But overall it seems like a noble failure. I’ve learned a lot in the process. My editors and I discussed at length why Building Gods hadn’t come alive. There was nothing inherently wrong with the original concept, or the dramatic setup. What was missing was something more elusive – that X-factor that lifts a story off the page and makes it real in the reader’s mind.

So why was it missing that vital spark? Ultimately, we decided, it was a mismatch between story and storyteller.

Anthony pointed out that one of my key skills as a writer is my ability to conjure an imaginary world. In my Blind Bowman novels, the primal forest of Sherwood was almost tangible in its sensory detail.

Building Gods was essentially a thriller. Written in first person, present tense, it prioritised pace above description, plotting above characterisation. It afforded me little chance to build a richly textured world. In short, in didn’t play to my strengths.

But it goes much deeper than that. The best elements of The Blind Bowman are the fantastical, the mythic – the squabbling of the old gods in the enchanted forest, and the demonic forces that play games with human lives.

Building Gods, set in a more mundane world, had none of these flights of fancy, none of these wondrous layers. More than anything, the story felt cold and shallow, as soulless as the A.I. machines driving its plot.

Perhaps my novels, to really catch fire, need to venture into more wondrous realms, to invoke the gods and summon devils and conjure magicks.

But if fantasy is my natural territory, why Building Gods? How did I end up even attempting to write a high-concept thriller?

This brings us to the source of the problem. And it’s a question, I think, of faulty motivation. Of all the half-formed stories floating through my imagination, the reason I latched on to Building Gods, if I’m being entirely honest, is because it was the one I thought might prove most popular.

I could already see the front cover, and envisage the quotes comparing it to a Blake Crouch thriller. I could imagine it being made into a film by Christopher Nolan.

All these things were warning bells. But I wasn’t listening. Because like most writers I’m tired of my stories not being seen. So I set out after this story with at least one eye on commercial success.

To make a long piece of fiction really come alive, it needs to be driven by a deeper passion. You must inhabit it with every fibre of your being. It has to obsess you to the point where it becomes as real as your day-to-day life.

Building Gods simply never spoke to me on that level. Therefore the prose remained workmanlike, the story flat and stale.

I think it’s particularly telling that since ditching the manuscript my overall sense is one of relief. I’m no longer obliged to work on a story that never set my imagination on fire.

In fact it feels cathartic. As if I’ve cleared away something shiny and seductive but ultimately worthless, freeing up space for a story of true value.

What that story might be I’m not yet sure. Once again, several half-formed ideas are flitting around, bidding for my attention. I’m getting on with some general research and waiting to see which way I’m drawn.

Only this time I’m staying doubly alert for siren calls: any voice that whispers “This one will bring you fame and fortune.”

Instead, I’m going to write the story that burns to be written, and let everything else take care of itself.

Thanks for being here – and happy reading!

Tim

P.S. Usually, the only thing to do really is to battle on to the end!

P.P.S. I’m not the only author who feels most at home writing fantasy fiction. Living legend Philip Pullman told me he feels the same way:

P.P.P.S. Here’s the great essay by

where he talks about finishing things. Advice that still has great merit in spite of everything I write above!

Glad you had the gumption to put it aside. That may have been harder to do than actually finishing the story.

I hope not all writing has to be cathartic 😅. It’s emotionally draining when writing is more consuming than real life.

If you wrote 100 pages don’t you think there’s something there? Maybe it needs another angle, another voice, maybe make it a fantasy! Did you read The Broken Earth trilogy? It starts like fantasy but it’s all science… mind-blowing.