I wrote a sentence, right at the end of my latest novel, Wildwood Rising, which seemed to me about as good as it could possibly be. This is a rare experience. In the course of writing four books, it has happened perhaps a handful of times.

Mostly, as far as I can see, writing prose fiction is a series of small defeats. You write a sentence as cleanly and clearly as you can, then you go back later to improve it, then you tweak it and polish it some more – until finally you admit it’s time to move on our else you’ll get stuck here forever.

Mostly. But not always. Just occasionally, out of the blue, a sentence will fall onto the page which appears…well, just about perfect. You hardly dare touch this pristine thing in case you mar it with you grubby fingerprints.

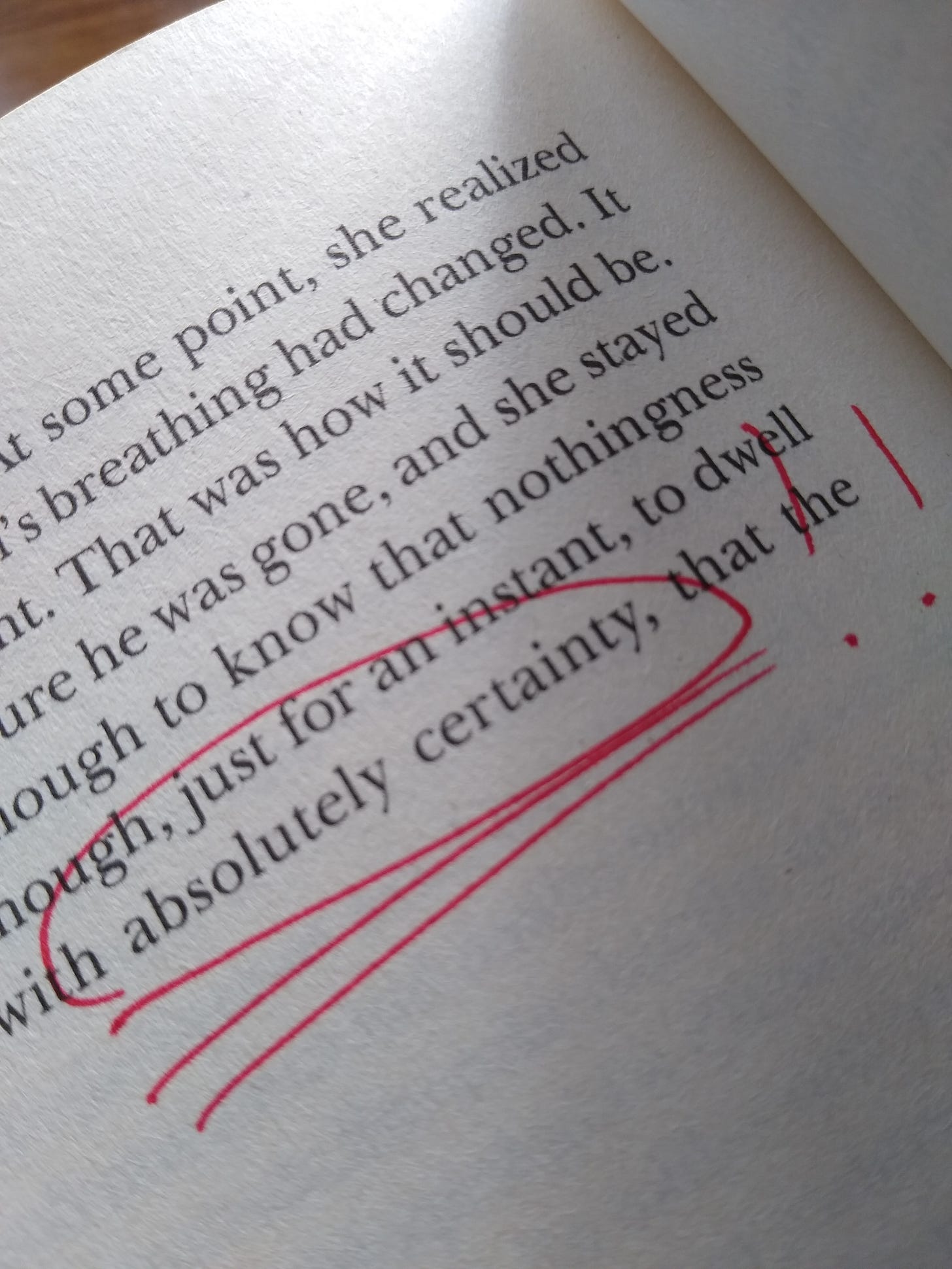

With Wildwood Rising, this chanced to happen at the best possible moment. In the penultimate chapter, the very last time we see our heroes Robin and Marian, as we prepare to say goodbye to them after three volumes, 1200 pages, there dropped a sentence that was sublime. In rhythm, in concision, in precision, it synced perfectly with the emotion of the scene and made the whole thing shine. I wasn’t the only one who thought so. In his notes on the manuscript, my editor Anthony highlighted this sequence, saying: “This is proper writing!”

I was proud of that sentence. Yes, damn it, I was proud. I couldn’t wait for the finished book to be out in the world just so people could drink in this one lovely, heartrending piece of prose.

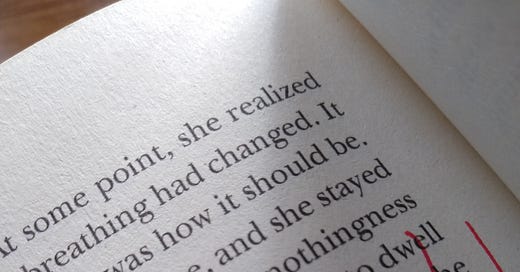

And then the first copy of the novel arrived – and my wife Lizzie was the first one to read it – and when she reached that glorious climatic sentence she stumbled over a glaring typo.

Instead of “absolute certainty”, the finished text now reads “absolutely certainty”. It cracks the cadence into pieces, leaves the meaning shattered.

How this could have happened I have no idea. My publisher, David Fickling Books, is renowned for the care and attention it lavishes on every one of its titles. The manuscript had been pored over by editors and proof readers. The typo wasn’t in my original text, nor was it in the proof pages we all scoured for errors. I can only think it crept in during the typesetting.

Not that it matters how, particularly. This isn’t me looking to lay blame. A novel is a complicated object, and there has never been one that didn’t contain a typo or two.

Nonetheless, I can’t help feeling aggrieved that this should have cropped up here, of all places, in the one sentence I considered immaculate. When we first discovered it, it felt like the universe was laughing at me and my puny efforts.

Perhaps it is. Or maybe it’s trying to teach me a lesson. A lesson about hubris, and humility. A lesson that the writing life has been trying to teach me from the beginning.

Simply put, the lesson is this: there is no such thing as perfect. Even when you think you’ve produced something flawless, the world will have other ideas. Our job as artists, and as human beings, is to get used to the fact that everything has a crack in it. That everything is compromised. We accept this, unconditionally, then carry on regardless.

Because what’s the alternative – to throw up our hands and declare that everything is impossible, so why try?

There have been times, in my writing life, when my obsession with perfection – or rather my fear of imperfection – has left me petrified. I’ve sat there endlessly rewriting sentences and scenes while the story went nowhere.

Back then, discovering this typo would have sent me into a tailspin. A tiny error – yet the part of me that carries shame and only wants to hide would have judged the whole story ruined. It would have made me tighten around my writing, becoming even more obsessed with making sure every comma is in the right place, thereby freezing future progress.

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

Leonard Cohen, Anthem

Now, most of the time, I can see that there’s a balance. We don’t want to make do with every half-formed thing that appears on the page. But at the same time we need to recognise the limits of what’s possible, and to remember that something good and finished is infinitely preferable to something perfect that will never exist.

I’ve read that potters in ancient Japan used to intentionally put hairline cracks in their vases to signify their acceptance of this: that although we may aspire to excellence, it is futile to strive for flawlessness.

That’s how I’m trying to regard that typo at the end of Wildwood rising. It’s the crack in my vase. It’s a reminder to forget the ideal and get on with making what’s real.

What about you? What’s your relationship to perfectionism? Spotted any glaring errors in your own work recently?!

Thanks for being here – and happy reading,

Tim

Hate to see that happen!

I once had an article I'd edited probably ten times, and had another half-dozen people proofread. We thought it was pretty perfect and sent the file to the printer. A few days later, we were asked, "Did you really want the apostle Paul to say, 'Fight the food fight of faith,' on p. 12?" All those eyes and grammar checkers missed it!

I abhor typos, but like you say, it's hard to write 100,000 words and not have one in there somewhere... I recently had a day-job typo go to print. Same thing -- lots of people reviewed before it was sent out. But it all falls on me, as far as I'm concerned.

The light in the crack of this one? Fitzgerald's first edition of "The Great Gatsby" is identified by its typos. Future generations will know they have a first edition of "Wildwood Rising" by that typo.

Know, with absolutely certainty.