An ancient proverb states: “When the student is ready, the teacher appears.” It might be equally true to say: “Until the student is ready, the teacher will be wasting their breath.”

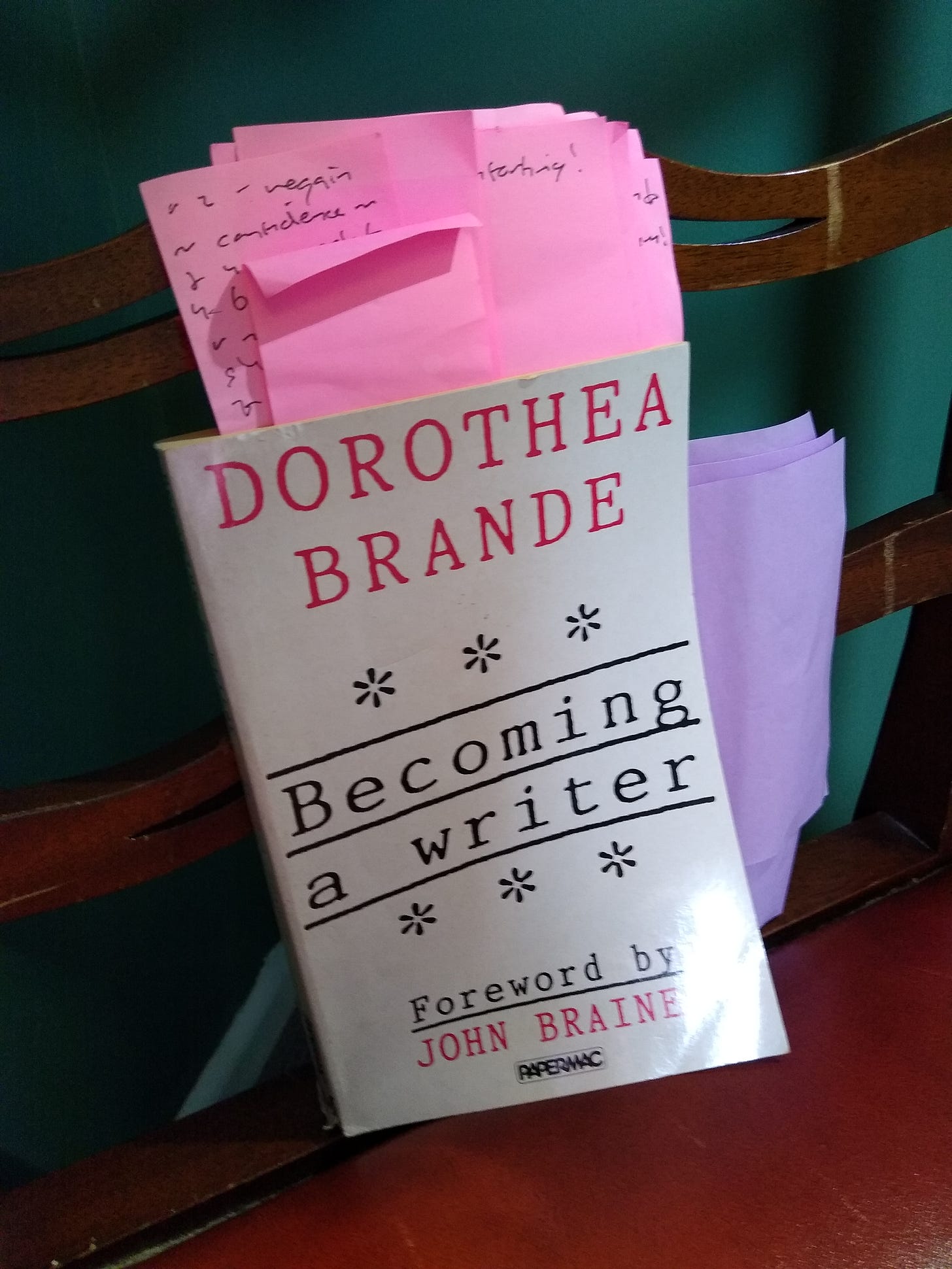

When I first read Dorothea Brande’s classic text Becoming a Writer, I didn’t get it. At the time I was journalist who yearned to write fiction. What I wanted was concrete, actionable advice about how to develop characters and structure acts and build believable settings. Brande’s book seemed to offer only abstractions about “harnessing the unconscious” and “inducing the artistic coma.”

In my defence, the book was first published in 1934, and can come across as mannered and uptight to the modern ear, with Brande’s voice making you feel a bit like you’re being told off by Mary Poppins.

In any case, this wasn’t the book I was looking for, and I cast it aside with disdain.

Fast forward several years, and I found myself in trouble. I’d signed a book deal, and had one novel published. But my follow-up had floundered. I was writing and writing but getting nowhere, the story becoming ever more tangled.

I presumed the problem must be a technical one. So I went back to all my old books on storycraft, re-educating myself on the basics of narrative structure and pacing and character arcs. None of it got me unstuck.

Finally, in desperation, I re-read Becoming a Writer.

And this time it clicked. At last I was ready to understand what Brande was trying to tell me: that no amount of studying technique will help a writer flourish unless they first master the psychology of writing. Or, in her own words: “Becoming a writer is mainly a matter of cultivating a writer’s temperament.”

Rereading the book in rapture, I could barely believe I’d ever considered it irrelevant. This time, in fact, it seemed to be aimed directly at me. In a section headed ‘The One-Book Author’ it talks about writers who have “had an early success but are unable to repeat it.”

Brande says: “It is evident, if this writer had a deserved success, that he already knows something, presumably a great deal, of the technical end of his art. His trouble is not there…no amount of counsel and advice about technique will break the deadlock.”

Ah…so then, what would get my writing flowing again?

At the heart of Brande’s message is this: a writer is not one person but two. They consist of a childlike, playful, artistic self; and also an adult, responsible, reasoning self.

Perhaps that doesn’t sound so revolutionary. In modern times we’re well versed in ideas about the left brain versus the right brain; logic versus emotion.

But Brande goes further. She insists not only that these two sides of our personality exist, but that in order to do our best work we must consciously and deliberately treat them as separate entities. Or, as she puts it, we must “split them apart for consideration and training!”

This was exactly what I needed to hear. I finally saw what had been happening: when I sat at my writing desk, the wrong part of my personality had been taking charge. Rather than dreaming with my childlike self, I had been measuring and assessing with my reasoning self. Every time I wrote a sentence – or sometimes before I had even written a word – that critical part of my personality had been immediately judging it not good enough and insisting I reconsider, or start again. This is the definition of creative fear, and the death knell of any artistic act.

What I needed to do, in order to rekindle my storytelling powers, was twofold. Firstly, I needed to learn how to switch off my reasoning self when it wasn’t needed. Secondly, I needed to rediscover, nurture, and fully inhabit the childlike, uninhibited, imaginative part of my being.

In Becoming a Writer, Brande suggests ways to achieve this; a quirky system which involves lots of lying on the floor and taking hot baths and long walks.

Over time, I’ve developed methods that are more effective for me. Three practices in particular have proved invaluable:

Meditation:

There are deeper reasons to meditate than to become a better writer, but there’s no doubt that meditation and storytelling play well together. My daily meditation practice helps me notice when my critical self is rising at an unhelpful time. When this happens I can gently tell him: “You’re not needed right now. You’ll get your say later. For now let’s see what emerges.”

A ‘Dreaming Draft’, written in freehand:

I label the first pass of a story the Dreaming Draft to signal to myself that this is not the time for logical thought; rather it’s time to get lost in imaginal realms. The only real rule at this stage is to write and keep writing, always moving forwards even if what’s coming out is basically nonsense.

Crucially, at this stage I steer clear of machines. A word processor is rigid and efficient – the antithesis of dreaming. Instead, I draft using pencil and paper. My hand is free to roam about the page – another powerful signal to myself that this is a time of exploration and play, when anything goes. These first drafts can be a mass of scribbles and annotations, and that’s okay.

I reassure my reasoning self that he will get a chance to tidy up the mess during the second pass, the Reading Draft. This is when I transcribe onto computer, ordering the raw dream stuff into something more intelligible that I can sit back and assess while also sharing with my agent and editors.

Writing chair and editing chair:

In Becoming a Writer, there is a section headed: “At the Typewriter: Write!” Brande says: “If you steadily refuse to lose yourself in reverie at your worktable, you will be rewarded by finding that merely taking your seat there will be enough to make your writing flow.”

This is advice I’ve taken to heart. During the Dreaming Draft, the moment I sit at my writing desk my pencil begins moving across the page. If I find myself pausing for more than a few seconds I get up and go and make a cup of tea. When I return, if I’m still stuck, I’ll go for a run or a walk.

I refuse to sit at my desk thinking, because I know from bitter experience that sitting there thinking kills a story stone dead. Story stuff bubbles up from the unconscious, and rational thought plugs that wellspring at its source. So at my writing desk I write; never plan, plot or edit.

Once I’ve transcribed onto computer, I print out the pages and take them to a separate corner of the room. Here, in my editing chair, I give my reasoning self free rein to take stock of what we’ve got – to assess and rework and refine as much as he likes.

If we are to make good work, our inner editor has a vital role to play. This part of us drives iteration and points the way to a more powerful story. But I would say that in our ultra-materialist, performative culture, most of us have little trouble contacting that critical part of ourselves. It’s the childlike dreamer that gets neglected. That part of us is timid and vulnerable and needs reassurance and nurture in order to make anything worthwhile.

How about you? Do you have methods to help care for your creative self?

Thanks for being here, and happy reading!

Tim

P.S. Talking of writing drafts in freehand, I did a live chat on that subject with the brilliant

and . If you missed it here’s the recording:Pencils and pens versus keyboards

Thank you Anthony Lee Phillips, MaKenna Grace, Joanna Sakievich, Simon K Jones, and many others for tuning into my live video with Meg Oolders and J.E. Petersen! Join me for my next live video in the app.

P.P.S. I’m far from the only writer who’s rediscovering the joy of writing freehand.

recently wrote a great piece on the same theme:

"They consist of a childlike, playful, artistic self; and also an adult, responsible, reasoning self."

My wife might argue against the second half of that statement... lol

Seriously though, there are times when I wonder into the kitchen for another coffee or something, and apparently have a whole conversation with her later that I never remember. When I'm in deep writing mode, my mind is still stuck in that gear when it should be engaging with the real world again. Unfortunately, that writer's mind has picked up the skill of *pretending* to be in the real world rather than where it really is: stuck in la-la-land.

I love the concept though. This is what I keep saying (but never in this way): you need to play when you're writing. Too many of us -- and I've been guilty of this for sure -- sit down to "serious writing" and end up going nowhere...

"Story stuff bubbles up from the unconscious, and rational thought plugs that wellspring at its source." What a great way to frame creative flow, and a reminder that "thinking more" won't help you get done what needs to be done. This really validates my habit of leaving my desk too! My puttering about isn't a distraction, it's me giving my unconscious space for the story stuff to bubble up. Great post.